Yesterday I completed (I use the term loosely) a C drama which was an odd mix of a police procedural-courtroom and melodrama. It was odd to the point that it felt at times that there were two different dramas locked in an almighty contest for oxygen. These sorts of problems have been par for the course especially where C dramas are concerned because of the ridiculous and arbitrary imposition of episode limits which are more about finance and logistics than anything about quality storytelling. Strangely enough (in my case) it wasn’t the police procedural or courtroom aspect of the show that got my attention because that tended to be formulaic and preachy but it was the male lead’s revenge plot which was by far the most addictive aspect to the show. There are plenty of criticisms that could be levelled against this drama that can be said about any C drama longer than 25 episodes but that would be a poor use of my time. What did hold my attention with the aid of fastforwarding is the revenge plot set into motion by the male lead as he joins an established law firm and begins impressing all kinds of people with his negotiation skills. It’s a disguise of sorts. What most don’t know is that he’s out to find the mastermind behind the accident that saw his parents die and him barely escaping the jaws of death. It’s not the most original premise but his behind-the-scenes maneuvering was sufficiently entertaining to keep me going.

Revenge dramas are fun. Some of the best Asian dramas I’ve seen in the last decade are shows about individuals who have legitimate grievances that cannot be addressed through the usual judicial processes for a swath of reasons. The rule of law… even if the context allows for it… has been hijacked or captured by vested interests because of the power structure that’s in place and the corruption which ensures a kind of gatekeeping. Justice cannot be achieved by people playing nice.

What I’m thinking about here isn’t strictly vigilantism although there are obvious overlaps because the key players see themselves as agents of justice working outside the parameters of the system that is completely broken. The difference for me is that those who are in the vengeance business play the long game. It takes years of scheming before their plans are set in motion. They ingratiate themselves with the culprits and embed themselves in the system with the purpose of undermining it from within. While they help others along, there’s a strong personal element. There’s also a strong element of danger because the villains are generally desperate to cling to power at any cost. Their agenda is such that they think themselves above all the normal legal or social restraints that binds the rest of us mere mortals. This is what makes them truly loathsome. The man and the woman who can stand against that sort of evil has to be single-mindedly of strong character with a particular skill set.

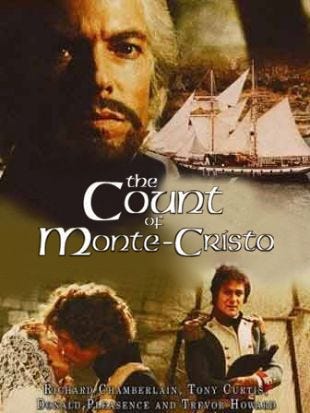

Of all of those that belong to that oeuvre, the one that stands above the rest is the first Nirvana in Fire or Lang Ya Bang. Widely lauded as one of the best C dramas of all time, it has enjoyed both critical and popular acclaim. For a hundred good reasons. For me it isn’t just the best C drama I’ve ever seen, it’s also one of the best dramas I’ve seen in any language. The best part is that while it directs plenty of nods at The Count of Monte Cristo, it is entirely its own beast. While it took me three episodes to really appreciate the cleverness of the writing, once it dawned on me what it was that I was dealing with, I was hooked. Some of the best television I’ve ever seen emerged somewhere in the middle of the drama which saw me clinging on to the edge of my seat nervously. Once you have tasted the Nirvana in Fire experience, few, if any, C drama are its equal. Luckily for me I came a little late to the party so waiting for new episodes to drop was not an onerous task.

The protagonist Mei Changsu is an antihero who is only too aware of the moral dilemma that clouds his mission. Deception and manipulation are his primary weapons and having an intellect that surpasses everyone in a wide-ranging battlefield certainly helps things along. He’s also had time to plan and establish a reputation that gives him access to the highest in the land. But he has his Achilles’ heel. Due to an incident that saw the death of his father, his army and his own near-death experience, the only recourse open to him is to inhabit the identity of a scholarly strategist which he uses to great effect. Of course Mei Changsu has help from his loyal friends but he is a sickly egghead living on borrowed time. His disguise works for him in large part but it also works against him when he interacts with those who knew him best.

It isn’t just redressing grievances that propels his ailing body forward but a deep patriotic desire to see better things for his country. As the story progresses a compelling case is made for sweeping changes top down. The rot set in a while back and the entire structure is crumbling. Under the current leadership corruption has been allowed to fester to detriment of political stability. The wrong kinds of people are holding on to the levers of power and the monarch rules with suspicion and ego rather than for the greater good.

Although revenge dramas can be considered a staple in K dramaland, not all are equally well executed. A favourite would have to be the well-acted and wonderfully written Money Flower. It also happens to feature another favourite, Jang Hyuk. I don’t instinctively reach for melodramas as part of my regular viewing pleasure but this is one that managed to engage me from start to finish with its world building and plotting. Moreover, this is also one that follows Dumas’ famous template closely. Like other antiheroes of his ilk, Go Pil-sik is a master of details with an eye on the trophy. As we bear witness to his journey, it’s evident that he crosses far too many lines Yet, he’s never unlikeable because of what he’s up against and what it ultimately costs him to succeed. Achieving his goals comes at a high price for a man who is narrowly focused on the mission at hand. It is as much a story of unspeakable suffering as it is a story of one man’s quest for recognition and justice. While in search of the justice that seems elusive, he also finds his redemption.

What seems to make The Count of Monte Cristo a classic to emulate is the way it humanizes protagonist Edmond Dantes even while he’s dogged in the execution of his agenda. On some level his achievements in dealing with his enemies are both awe-inspiring and terrifying. At the end of it all, however Dantes is merely a broken man (not necessarily the instrument of God that perceives himself to be) who needs to forgive and move from the past. Yes, those people who destroyed his life were reprehensible and in all likelihood deserve what was coming to them. There’s no denying however, that vengeance can have adverse effects for those caught in the crossfire as well. A good revenge story doesn’t sidestep any of that. Targets get hurt which no doubt is the point of the exercise but inevitably other people around them are drawn into the dragnet. A story worthy of being read and adapted even almost two hundred years later must have done something right with characterization and storytelling. Much more than that it is a deeply religious story about the systemic effects of sin, redemption and forgiveness. From the time Dantes discovers what’s been done to him while he’s imprisoned in Chateau d’if to when he sails away with the prospect of a new life, he learns that despite the power he thought he had to determine life or death for others, he is just a man also in need of atonement and love.

All this begs the question — what makes revenge stories attractive? There seems to be a universal appeal to them. To me the appeal (at least in part) comes from an innate desire to see justice done against all odds. C.S. Lewis in Mere Christianity gives examples of natural law at work. The idea of fairness even among children is interesting. I am also of the view that the revenge narrative is a reminder to us of our frailty as humans and our desire to have power over our enemies. It’s the fantasy that we can control the world… our world except that when we exert control, we must be prepared for the unintended consequences that result. It is also in part about the manichean battle between the forces of good and evil. Evil does exist, no matter how unfashionable it is to think that way. One however can believe in evil without demonizing one’s opponents unless one is referencing the father of lies himself.

There’s no doubt that our fascination with the revenge narrative is very much tied to our sense that we live in a deeply moral universe. It’s for me a healthy rejection of nihilism. Something’s gone terribly wrong and someone needs to put it right. But who should be our saviour is the besetting problem because we have the tendency to pick the wrong ones. It seems that the revenge story allows us to play out those existential ideas in a safe way while acknowledging that even those who have the best of intentions are flawed broken humans with have a tendency towards hubris which can sometimes lead to the cure being worse than the disease.

I am not sure Nirvana in Fire can be taken as an example of a revenge plot. The idea of 'making them suffer for the pain they brought to me\my family' seems too narrow to fit Mei Changsu. His view of 'bringing justice to the dead' focuses probably on clearing their names and protecting their families from further prosecution. Dealing with the culprits is rather a means to an end than an ultimate goal