It took us 3 weeks to finish this and last night we finally sat down to the last couple of episodes. It wasn’t for lack of interest that this was put on hold but a case of trying to find the time while doing life and other dramas. I became acquainted with Lee Jung-jae during my watch of Chief of Staff and Park Hae-soo of course from his memorable stint in Prison Playbook. The calibre of the actors was enough to get us started on this modern day battle royale that preys on desperation and greed in disquieting fashion.

As far as K dramas are concerned, it does well enough. It’s not the best K drama I’ve ever seen but it certainly offers much food for thought for those who can stomach the violence even while squirming uncomfortably in their seats. At its core, it’s not an especially original idea for those who have followed the Liar Game franchise and the Korean adaptation of that series. When my kids ask me what it’s like, I say it’s Hunger Games doing morbid things with children’s games. That said, this recent offering from K dramaland is clearly leaving its footprints in familiar territory. While the underlying message fall along similar lines, it is far more brutal… much more macabre — turning beloved children’s games into blood sports. If we ever needed any more proof that human beings are capable of terrible deeds in the name of wealth and prosperity, this drama provides it in spades with enough visceral fodder to last for some time. The results are bloody, messy and exceedingly ugly. A well-known piece of wisdom from the New Testament might be what the writer had in mind — “For the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil.” — when he penned this tale of human depravity.

It’s not hard to come to that conclusion. For those behind the game, for those watching this terrible spectator sport reminiscent of gladiatorial combats in days of old and contemporary voyeuristic reality television, there’s an implied perverse pleasure in seeing “lesser” beings duke it out to the last man standing. The fabulously wealthy have the resources to fund their deviant whims and the financially-strapped have sufficient motivation to risk it all for the prize money. The gamification of life and death is a profoundly troubling idea although it points (not entirely) allegorically to the kind of soul destroying dog-eat-dog rat race that many are inevitably a part of.

Even if he’s the protagonist and the show’s primary lens, Seong Gi-hun is hardly an attractive personality by any criteria. Lee Jung-jae does a superb job of making it hard for us to root for him… at first. The word deadbeat was invented for the likes of him. From the word “go” the man is a parasite, leeching off his long-suffering mother, unemployed and divorced. He is aimless, not especially bright and is about to lose contact with his ten-year-old daughter. While it’s certainly the case that life hasn’t been kind to him, he continually makes poor choices. Seong Gi-hun is also an inveterate gambler which is the hook that leads him to be embroiled in Game Inc. To be fair to Gi-hun, it should be said that there aren’t that many likeable characters in this show. There’s a very long line of candidates for the role of villain because it isn’t just about four hundred plus people battling for the contents of an oversized piggy bank. It’s really all about survival. “Skin for skin! A man will give all his has for his own life.” (Job 2:4)

Apparently he’s not the only one with money issues who is looking for a quick way to earn some easy cash. Except that winning is far from easy. There are multiple bus loads of “volunteers” who make their way to a mysterious facility guarded by armed men wearing highly visible protective body suits. When he arrives on site, Gi-hun comes across Sang-woo, a childhood playmate from his neighbourhood, an SNU graduate who has seen much better days.

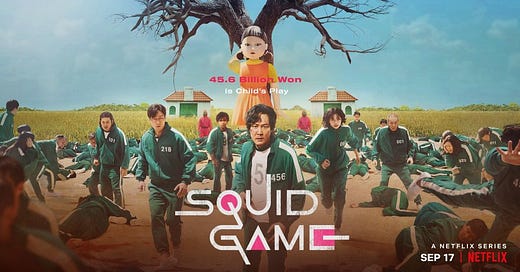

It comes as a rude shock to the participants when the first game begins that elimination from the game really does mean elimination in extremis. During a game of Red Light, Green Light a large doll that swivels around equipped with movement sensors detects anyone who moves and and the offending individuals are immediately shot on the spot. The dead are then morbidly carried out in a coffin in the form of a gift-wrapped box. I mention this because the juxtaposition of props related to childhood with untimely death seems paradoxically and cynically grim. All of this sets the stage for a chilling unease that never leaves you.

A large part of the awfulness of the games isn’t just the expression of human greed on display but the kinds of choices/dilemmas that are foisted on the contestants. Ultimately it’s not necessarily about strength or even intelligence winning the day but individuals having a ruthless determination to win at all costs. Teamwork means little in that arena as they are largely about forming temporary alliances to overcome immediate obstacles. Each round can see allies quickly turn into opponents in a battle of wits. These shifting states of relationships shows the results of a universe not governed by notions of good and evil, a bedrock of first principles but expediency. Nobody matters except as a means to an end. There’s even time to feature a sexual encounter in the rough and tumble of making strategic calculations but like all other unions it’s purely transactional and perhaps even illustrative of the old adage that “hell hath no known no fury like a woman scorned”.

In short, playing (and watching the game) is a dehumanizing experience. Here men and women aren’t rational beings made in the image of God but hungry beasts tortured and exploited for sport. It’s survival of the fittest writ large. The analogy of horse-racing comes up in the course of the drama — a picture which speaks to Gi-hun who was a regular punter at the race track. It seems ironic too that a man who had long forgotten about responsibility is gradually nudged by an inner voice to take responsibility for strangers. In the process of fighting for his own survival in this blood sport, he regains a smidgeon of his humanity and sees the humanity in others.

The most religious person in the motley crew of players doesn’t fare well in the scheme of things. For someone who purports to be God’s earthly representative he’s a repugnant fellow whose faith is skin deep. He is much mocked and everyone wonders why a former man of the cloth is even taking part in a battle royale for cash. It’s clear to all especially the cynical Ji-yeon that fear not faith is what drives his prayers. Later we discover too that she has a personal axe to grind with men of faith. Her place in this contest though minimal is important as the show intimates that even in this mire of competing agendas that she might be much closer of an example to the Christian ideal than an overtly religious figure despite her agnosticism.

There’s an old proverb I learnt as a child: In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. In Squid Game, that man is Gi-hun. While it is established early on that he is a deeply flawed creature, he isn’t the worst. In fact, it is somewhat surprising that his conscience (a commodity very much in short supply among the gamers) is still in play but that could well be the unexpected benefit of being simple-minded. For the audience, on the other hand, it’s a reprieve from the exhausting effects of the egregious nihilism that pervades the atmosphere.

I hear that it’s become an international sensation — a notion that’s baffling to this seasoned K drama watcher. While the storytelling is not bad and the performances are reliably good., it’s not the kind of drama that I would be recommending to my squeamish lady friends in a hurry. Perhaps its success is more a reflection of the times that we live in and the writer-director has astutely captured the zeitgeist. I can only speculate that the unpredictability of how the character arcs are resolved speaks to the tumultuous times we live in and provides some kind of momentary catharsis and escapism.

I get the sense that people are watching it not as a "K-drama" or even an Asian drama but an international Netflix drama, which is probably helped by the fact it has English dubs. I was surprised by how many people in North America were referencing and commenting on Squid Game, though I personally don't have the stomach for it. My guess is that it hit all the right notes of morbid fantasy and the evils of modernity/power with somewhat relatable premises (since everyone has played childhood games) that are spun in a Korean way that is different enough to have it stand out from similar movies/series. And it lends itself well to the rabbit hole of how far evil can go or how much the relative innocence (of the games/people) can be corrupted, which is fascinating to many and certainly even to a little voice at the back of my head.

Though I'm not sure I will ever watch it, I'm really glad the actors involved are getting more recognition (Park Haesoo looks so different with hair hahaha. It seems like they all did an amazing job.

Thank you for this review. I was really wondering about the popularity of this series.