This post was prompted by comments I’d seen on other platforms critical of those early episodes of Love Like the Galaxy accusing them of being “slow” and “unnecessary”. In large part this is a defence of those episodes which are absolutely foundational to the entire drama even up to the most recent episodes. At the time of writing, I haven’t yet watched Episodes 25 or 26.

It’s safe to say that most people if they’ve ever heard of Pride and Prejudice immediately think of the romance between Elizabeth Bennet and Mr Darcy. Thanks to the popularity of existing adaptations and an assortment of fanfiction homages, that impression persists. It’s even become the template for hundreds romantic comedies since its publication — the male and female lead start off their journey with a highly unfavourable first impression of each other until something happens which leads to one (usually the male lead spending unexpected quality time with the female lead) changing his/her mind about the other. It’s become a trope and its appeal is unerringly universal. While I would never deny that the romance is what drew me in as a teenage girl, Jane Austen’s most famous novel is much more than a historical romance. Much much more.

Don’t think so? Just consider how Austen opens the novel:

“It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.

However little known the feels or view of such a man may be on his first entering a neighbourhood, this truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding families, that he is considered the rightful property of some one or other of their daughters.”

In two sentences brimming with wit and irony, Austen states her intentions with undeniable clarity. The book is first and foremost a gentle and yet blistering critique of the world that she inhabits while positioning herself as a somewhat dispassionate but amused observer of the all too human foibles. Every world is governed by rules — some spoken, others unspoken — because there’s a moral order that has to be maintained lest that world descends into chaos. More often than not those that are unspoken have more sway than those that are. However, these rules or assumptions about the moral and social order are not always adhered to even while everyone on some level pays lip service to them. In this case marriage is a given for women. Marriage to a wealthy man is also a given but the pickings are slim so the law of supply and demand applies. Competition means that there are games that have to played and hoops to jump through. Because of the dictates surrounding primogeniture, a rich young heir is “permitted” to marry whoever takes his fancy but the second son of an earl has to be much more discrete and find a wife that can support his lavish lifestyle. These are the unwritten rules of Austen’s day for marriage apart from the requirements of chastity before marriage and all other manner of Christian virtues.

Because unspoken rules often dominate the landscape, it is clear that moral ideals get left in the dust as pragmatism rears its head. The institution of marriage is just one casualty in all this. Laws that are given to protect not only become tools to elevate one’s position in society but is weaponized to assert control over the ordinary folk.

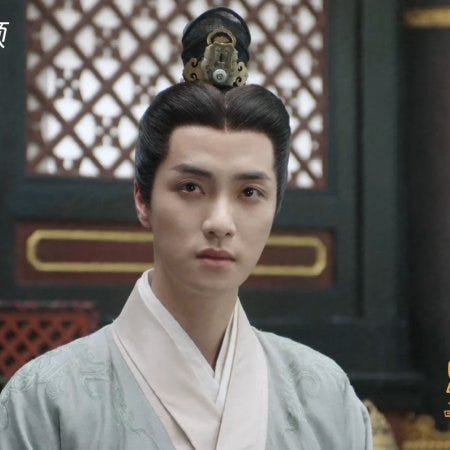

Love Like the Galaxy begins with all the familiar elements of a multigenerational family drama but it soon becomes evident through its use of satirical and hyperbolic devices that there’s something else at play. Beneath the veneer of respectability, there’s a something rotting inside the family cellar. There are rules aplenty to live by but in reality these are trotted out selectively whenever it’s convenient to assert an individual’s authority rather than to achieve an objective moral good. Rules are not about achieving harmony but is a mechanism of control and even division. One rule for thee but not for me. In fact among all known rules of the day, there is also a hierarchy of importance. For example, filial piety and respect for elders trumps illegal activities. Cheng Shaoshang is accused by her family of disloyalty when she turns in her Great Uncle Dong (Grandma’s younger brother) who is a participant in an armaments fraud case. This is a key reason why her mother is perpetually in fear of her bringing the family to ruin with her “reckless ways”. The fact that Uncle Dong has participated in a crime that has consequences for national security is secondary to the fact that his being found out will put the rest of the family in jeopardy. The weighting given to these rules in relative importance to one another is underpinned by expediency. This is also what immediately impresses Ling Buyi about the young Cheng Shaoshang who seems to be a budding non-conformist.

When Cheng Shaoshang’s mother returns from a long stint away from home, she firmly insists that her barely literate daughter study the classics so that she can learn to more virtuous in the shortest time possible. The illiterate Grandma, on the other hand, not only is culpable for leaving Shaoshang largely to her own devices and at the mercy of a scheming daughter-in-law but she’s an unabashedly greedy woman that hogs every kind of shiny thing that gets brought into the house. Despite that she’s indulgently tolerated by her sons and their wives Why? Because she’s the family matriarch that brought them up that her covetousness and silliness are tolerated? or perhaps they don’t think that old dogs can learn new tricks so the more efficient strategy is just to trick the old dog. Clearly the rules don’t apply equally. Seniority trumps all else. In order to handle her, they don’t appeal to the sages but play the same manipulative games that she does. When Niaoniao’s brothers informs her excitedly that they’ve brought her greeting gifts, their mother sternly admonishes them to consider their cousin Yangyang as well. On another occasion when Yangyang’s nanny covets Niaoniao’s new old desk and excrement hits the ceiling, Yuanyi kicks up a big stink (without getting to the heart of matter) laying the blame on Niaoniao for being ostentatious and then her twin brother for showing favouritism as if those are the animating issues behind this debacle. Later she chides the Third Sister-in-Law for being biased presenting Niaoniao with a nice red fur cloak while Yangyang doesn’t get anything from her. So how does Yuanyi rectify that? By paying excessive attention to Yangyang at the lantern festival at Niaoniao’s expense.

How is that, in the name of everything we know to be good, a good way to model justice and kindness to a 15 year old girl who is looking for guidance?

No wonder the poor girl is confused about this thing called virtue. It’s empty virtue signalling. There’s no consistency in the application of the rules. And they wonder why she’s cynical. All these so-called role models are sending mixed messages. Shaoshang is told to respect her elders but her elders don’t give unqualified respect to their elders or superiors for that matter. She is reprimanded for her cunning and yet the adults in her life are equally adept at it. Over and over again, she is humiliated and mocked for her lack of etiquette but the demur young ladies of the upper echelons who have been presumably schooled in all the right books are good at keeping up appearances but are not past using their position to bully those with a lower status.

There is no “rule of law” just a power structure in service of conformity. So while reading Confucius, Mencius and Lao Zi might be intellectually stimulating, (something for the scholarly types to interpret and reinterpret at whim) when it comes to day-to-day application, few take them seriously. Hypocrisy then becomes the order of the day. Soon such practices become entrenched to a degree that it becomes unspoken law.

This too is why Ling Buyi is drawn to Cheng Shaoshang. She is honest about herself. Honest self-reflection is refreshing in a place like Ruyang but dangerous in a world that’s comfortable with the lies that has become a part of the social discourse.

Despite the title Love Like the Galaxy isn’t a romance in the same way Pride and Prejudice isn’t a romance. Apart from being a coming of age story, it is also a poignant commentary of the world in which the characters inhabit seen through the inquiring lenses of its young protagonist trying to navigate its pitfalls only to find the rules of the game in constant flux. Grandma is scarcely a respectable creature. She is silly, vulgar, easily manipulated, superstitious and materialistic. Yet she has to be coaxed and placated to the point of exhaustion. She has to be threatened or handled but can’t be reasoned with. When it suits, Yuanyi can be disrespectful at opportune moments. Her tempestuous push back at the Lou’s household is not exactly the height of civility but somehow it’s acceptable because she does it to protect her daughter and to prove a point.

Whatever transpires in the Cheng household is only a microcosm of the larger society. There’s a humorous moment when the emperor rages on about the unruly, sacrilegious behaviour of the youngsters during the visit to Mt Tugao. His consort tells him it’s no big deal… just young people acting their age. She cites a time when as a much younger man he climbed a wall to visit her secretly. Slightly embarrassed he ticks her off for bringing that up. Not long afterwards, Cao Cheng runs in to announce that Zisheng has injured himself from rescuing Cheng Shaoshang. On hearing this, the emperor perks up and soon changes his tune about misbehaving youngsters and his misbegotten youth.

It’s almost as if rules are made to be broken.

The cracks are showing and while on the surface everyone seems to know their place, there are tensions simmering below the surface. Prosperity is merely a cloak. There is discontent in the air from the whispers of a conspiracy that we’ve been privy to. Hua County and Feng Yi are just the beginning. Not everyone is satisfied with the status quo. The third prince is ambitious. Zisheng wants revenge for Gu City. Officials abuse their power.

There’s something rotten in Denmark… or Ruyang. No civilization can survive on lies.

It’s a world that’s legalistic, hypocritical, contradictory and teetering on chaos. Clearly a major upheaval is in the offing.

i love that i wasnt the only one who is comparing the Cheng family with the Bennets haha grandma is so mrs bennet , after the bridge incident SS immediately blamed LBY for tattling on her , that is so Lizzy . miss perfect Yang Yang is Jane and i guess that will make the Emperor , Empress the Gardiners? hahaha now im casting everyone.

Impressive take-out, the comparison with P&P is so on point ( myself being in love with Jane Austen's novels...by the way, maybe someone will right a novel about Her life ! ). Enjoyed again your article, how about starting a novel on Wattpad for us, please ?